2 Hours/Week in Nature: Your Prescription for Better Health?

By Amy NortonHealthDay Reporter

THURSDAY, June 13, 2019 (HealthDay News) -- Spending just a couple of hours a week enjoying nature may do your body and mind some good, a new study suggests.

The study, of nearly 20,000 adults in England, found that people who spent at least two hours outdoors in the past week gave higher ratings to their physical health and mental well-being.

There could, of course, be many reasons that nature lovers were faring better than people who preferred the great indoors, according to lead researcher Mathew White.

White said his team tried to account for as many alternative explanations as possible: They asked study participants about any disabling health problems that might keep them homebound, as well as their exercise habits.

The researchers also looked at factors such as people's age, occupation, marital status and the characteristics of their neighborhood -- including poverty and crime rates.

In the end, outdoor time itself still seemed beneficial. People who spent two to three hours per week in nature were 59% more likely to report "good health" or "high well-being."

In fact, White said, even when people had health conditions, they typically rated their well-being as higher if they got outside at least two hours per week.

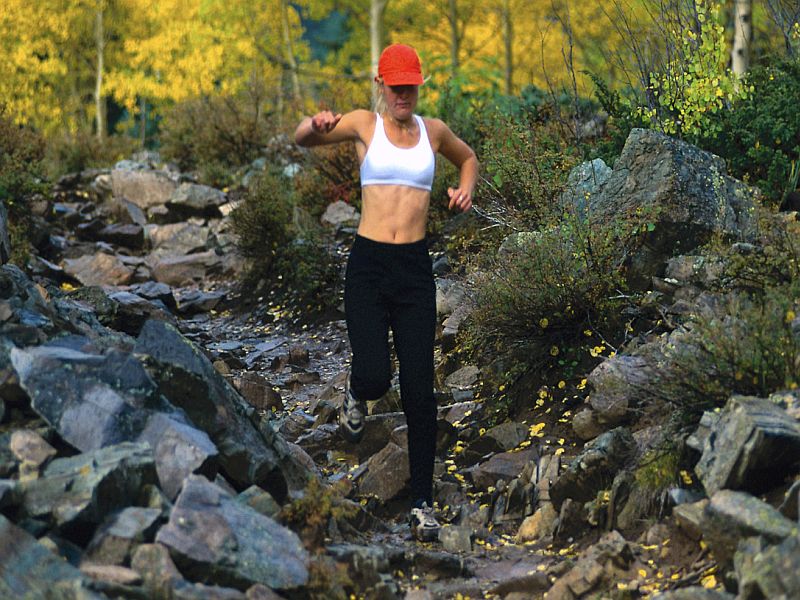

And that did not have to mean hiking a mountain, or even venturing far from home, according to White, a senior lecturer at the University of Exeter Medical School, in England.

Most people in the study got their outdoor time within two miles of home. So a trip to the local park or other "green space" will suffice.

"Get out in nature for two hours a week -- it doesn't matter where," White said. And, he added, it doesn't have to be two hours in one go.

That's an important message for people who think they don't have the time or resources for getting out into nature, according to Kathleen Wolf, a researcher at the University of Washington College of the Environment, in Seattle.

"In the U.S., I think, there's often a belief that to get out into nature, you have to travel to a national park," said Wolf, who was not involved in the new study. "But it doesn't have to be expensive, and it doesn't have to be hours in one shot."

In fact, she added, most studies on the relationship between outdoor time and human well-being have focused on "nearby nature."

For the current study, White's team used data from more than 19,800 adults who took part in a U.K. government survey. Among other things, participants were asked to rate their general health and satisfaction with their lives (a measure of well-being).

They were also asked how often they'd spent time outdoors in the past week -- be it the countryside, the woods, a beach or green spaces within a city.

Overall, a difference emerged at the two-hour "threshold." For example, among people who'd spent two to three hours in nature, 82% said their general health was good, and 65% rated their well-being as "high." Of people who'd logged no nature time, 68% rated their health as good, and 56% reported high well-being.

"What's interesting about this study is that it's getting at 'dosage,'" Wolf said. "It's not just, 'spend time outdoors.'"

Like all such surveys, she noted, the study has limitations. Even though the researchers tried to account for other variables, it's always possible there are explanations for the findings.

Still, Wolf said, many other studies have suggested that time spent in nature does the body and mind good.

A 2018 review of 140 studies found that, on average, people who regularly spent time in, or lived close to, green spaces had lower blood pressure, heart rate and levels of the "stress" hormone cortisol. They also tended to sleep more at night, and had reduced rates of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Wolf said it's not yet clear exactly how contact with nature benefits us -- that is, what does it do to the brain and nervous system? But scientists don't always know precisely how a medication works either, she noted.

Wolf thinks the evidence is compelling enough that community planners should be taking green space seriously.

"Parks are not just a frill," she said.

And those plans should include equitable distribution, Wolf added, so that green space is not only a luxury of wealthier neighborhoods.

The findings were published online June 13 in Scientific Reports.

More information

The U.S. National Park Service has more on nature's health benefits.

The news stories provided in Health News and our Health-E News Newsletter are a service of the nationally syndicated HealthDay® news and information company. Stories refer to national trends and breaking health news, and are not necessarily indicative of or always supported by our facility and providers. This information is provided for informational and educational purposes only, and is not intended to be a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.