Could a Vaccine Against Future Pandemics Be on the Way?

By Alan Mozes HealthDay Reporter

WEDNESDAY, May 12, 2021 (HealthDay News) -- An ambitious new vaccine effort is taking aim at future coronavirus mutations that may threaten global health down the road.

So far, the "pan-coronavirus vaccine" has proven 100% effective in testing among monkeys, investigators reported.

"Large outbreaks of coronaviruses have occurred three times in the last 18 years," explained study author Kevin Saunders, director of research at the Duke University Human Vaccine Institute in Durham, N.C. "They tend to occur about every eight to nine years."

And new virus mutations are almost certainly already out there, lying in wait for a chance to jump from animals to people.

They "can be found in wild animals … where coronaviruses that cause outbreaks circulate, until they have an opportunity to transmit to humans," Saunders noted. "Thus, we need a vaccine not only to end the current pandemic, but to also prevent future pandemics.

"Current vaccine platforms are targeted to blocking the virus that causes COVID-19," he noted. "A pan-coronavirus vaccine would block many different coronaviruses," and in doing so "protect you against the coronavirus that is causing the current pandemic, but also future related coronaviruses."

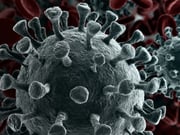

With that in mind, the new vaccine effort centers on what the study team calls the "Achilles' heel" of a coronavirus: a particular spot on the spiky surface of the virus that needs to bind with human cells to infect them.

The good news, said researchers, is that this spot is a vulnerable target, regardless of which particular version of the coronavirus is in play. In other words, it may be possible to block a wide variety of current and future coronavirus variants.

To that end, the Duke team fashioned a high-tech molecular weapon, composed of a tiny nanoparticle paired with a specific receptor blocker (called 3M-052). The molecular architecture of the pairing essentially takes a small piece of the existing coronavirus structure and generates multiple copies of it to shield human cells from coronavirus spikes.

The result: In monkeys, the pan-vaccine appeared to boost the immune response more robustly than either current vaccines or a natural coronavirus infection.

In fact, it blocked all infections without fail, regardless of whether the infection source was the so-called original human coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1) or any of the four most common mutations of the later viral iteration (SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19), including variants widely referred to as having first been spotted in the United Kingdom, South Africa and Brazil.

So far, the pan-vaccine has also proved 100% effective at halting infections involving animal coronaviruses that have not yet crossed over to humans.

"The results in primate model systems of COVID-19 shows the vaccine can completely suppress the virus that causes COVID-19," Saunders said.

Still, the immune response seen in monkeys can sometimes end up being less potent in humans, the team acknowledged. So Saunders and his associates stressed that clinical trials in humans will be needed "in order to know what level of response humans will have to the vaccine."

In addition, "we are exploring ways to broaden the activity of the vaccine such that it covers as many coronaviruses as possible," Saunders said. "We are also exploring ways to combine the current vaccine with rapid vaccine manufacturing processes already in use."

All these efforts sound like a good plan to Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar with the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore.

"Within the coronavirus family, there are several that have the ability to infect humans and some -- MERS, SARS, SARS2 -- that can cause serious disease," Adalja noted.

"Having a vaccine that targets more than one coronavirus can help remove them as a threat," he said. "There are definitely more coronaviruses that will emerge and have the ability to infect humans. So, this would be a proactive action to preempt [future] emergence."

The latest findings were published May 10 in the journal Nature.

More information

There's more on various types of coronavirus vaccines at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

SOURCES: Kevin Saunders, PhD, director, research, Duke Human Vaccine Institute, Duke University, Durham, N.C.; Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore; Nature, May 10, 2021

The news stories provided in Health News and our Health-E News Newsletter are a service of the nationally syndicated HealthDay® news and information company. Stories refer to national trends and breaking health news, and are not necessarily indicative of or always supported by our facility and providers. This information is provided for informational and educational purposes only, and is not intended to be a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.